Reluctance and Gratitude

October 6, 2024

The Call of the Badge

November 20, 2024Sailor’s Wisdom

It was enough to make a parson curse. Flat on my back, I had a brow furrowed with worry.

A man in serious trouble packs an equally serious potential for danger. He might react like a cornered, rank bull. He might be erratic, seeking any wild, panic-driven solution; any way out without regard to consequences. On the other hand, a man challenged with severe misfortune might be disciplined and resourceful, a pensive, creative and proactive man who seeks solutions first; a man who engages problem solving with an appetite.

Somewhere between those two extremes was where I found myself. I wasn’t one to panic, although I had something less than a healthy appetite for solving this problem. Searching resources and options, I saw no way out, no solution. But, the gnawing in my gut insisted I was in major trouble.

I had a ranch to run and a couple thousand head of beeves plus a remuda to winter. I’d just winter-furloughed all my hands but three. One was my wizened old cook. The other two were up on the high-mountain line shack for the winter, maybe snowed in already. Doc Wells said I needed to be abed for at least a month and probably two or more before my leg would be of much use. Breathing was a struggle due to my lungs being bruised by a saddle horn in that wreck on the bank of The Green River.

❖

My given name was Jeb Stuart Willoughby. Ma named me after the Confederate general who was her brother. I hadn’t much used that handle since leaving Virginia ten years ago. Now I found it rather a surprise when I remembered the fact that I actually had a full name. Most folks called me Will, or close friends maybe Willy, and I liked that just fine. I was an unmarried man, pushing into the downslope side of my twenties. Sitting on ol’ Sketcher on a tall knoll above the ranch house and barn, admiring the improvements that I had made to the place, I nodded to myself in satisfaction with what I had achieved so far.

Pa had learned me a lot that I put to good use to get a foothold on life. Living that life, which included more failures than wins in the beginning, had taught me still more. Experience is a helluva school marm.

One of those life lessons might have been described as, “Don’t go tryin’ to fix something that ain’t broken.” On a working ranch there was always more work than time for those things that needed fixing, so a man need not waste time on those things that were still fully functional. Also, those fixings that some might have called improvements would sometimes end up with the item being in disrepair or losing all function for a time.

I proudly owned my own small cattle spread, which I had claimed and settled on my own by buying some English Hereford stock and renting the use of a neighbor’s Mexican longhorn bull. By crossing the two, an idea I had learned from some smart cattlemen in Texas but which had not yet been tried around Rock Springs, I came up with a very disease-resistant, rangy, self-sufficient bovine that still put out good and flavorful beef. Pound per pound, it had been a great success.

I was a man alone. A man alone can be more efficient, more safe and move faster in the wild. He relies only on his self since that is all he has. But a man settled and ranching needs a helpmate. For me that meant partnering with a strong woman who packed some stick and ideas of her own to supplement mine. Pickin’s were slim in the territory when it came to womenfolk, so I was biding my time and focused on building a place that the right woman would find inviting - or at least acceptable. I was fixin’ to make my spread bigger and better, so I would be able to run more cattle and be ready for that lady and the family we’d muster when I found her.

Neighbors were moving on and selling out and I was a man of vision and ambition. Somehow I wanted two of the spreads that touched my ranch. Another that would be up for sale was more vertical than not and had poor grass and no water. I’d buy it if the price dropped some, but only for a buffer and as a place for logging trees for lumber one day. A lumber mill at this point would be a diversion from the main thrust of my business, a cattle ranch. Sure, it was a distant potential but at present would only be a distraction.

I was a mindful man, not inclined to rambling or waste. My days all began with a purpose.

❖

He never spoke of where he had come from, and it was a thing a man never asked. Clint Oakley showed up on the Flying W late one fall looking plenty used. He was so weathered, grizzled and worn, a man couldn’t tell if he was fifty or eighty but he sure had the look of being a long way from his prime. Yet, there was no suggestion of urgent need in his eyes. He carried himself with assurance, an inner stillness maybe.

He said he was hunting work. With winter coming, and a lot less need of hands, I had just recently let most of the boys go. I told Clint so. I didn’t tell him that I was also thinking by his looks that I didn’t expect him to be able to work much at all. He just looked at me with a kind but engaging stare out of those seasoned gray eyes. He didn’t respond verbally for a time. He just looked at me making me uncomfortable and pensive.

I guess I was the first to blink, because I finally smiled and asked him if he was hungry. He nodded, adding that he could do with some grub seeing as he hadn’t eaten in a while. His rail-thin body made me curious about his meaning of “a while”. It was coming on to supper, so I offered him to share our chuck. I might have been skeptical about his ability to work, but only a fool or heartless soul would turn away a hungry man. Ma hadn’t raised either of those.

I heard myself adding, “And you can bed here in the bunkhouse for a night too if you’re of a mind to.”

He turned his tired old plug into the corral and hung his worn old McClellan saddle on the fence. Then he fetched up a bit of dry grass and rubbed the old boy down while muttering soft sounds that I couldn’t distinctly make out, but they sure sounded like praise, gratitude and affection. He didn’t hurry. I admired a man who took the time to do well whatever he set about. I was a bit taken and so I waited for him and watched. He had demanded nothing and asked for little, but his humility was laced with a serious bunch of comfortable assurance.

When he was ready, he came to me and said he was right thankful for the offer of a meal. He then added, “By the way Sir, if you’d lap them rails so that they don’t all break on the same post, your corral fence would be a lot stronger and the posts not so inclined to sway or give way.” I’d never thought of that but looking at my corral fence now, it only made obvious sense.

❖

A hungry man takes eating seriously, talking little, if at all. The old man ate.

When Cooky brought out a plate of more chuck and offered seconds, Clint graciously declined. I took that as his respectful notion to not take advantage of generosity so I asked Cooky if he’d any of that specialty of his left. When he brought out a plate of bear sign, Clint did not refuse.

I was taking a shine to this old timer, and a curiosity too. He exuded competence, humility and gratitude, traits that, in these parts, were rarely found in combination. I wondered about him and so, trying to not be rude or disregard western privacy codes, I gently probed, expressing an admiring interest.

He smiled, the first time he had done so since arriving, and said, “A man doesn’t endure my decades without snagging some valuable experiences. If he has a care about folks, and maybe some desire for a legacy too, I reckon he ought’a be willin’ to pass some of those learnin’s along. No need to make folks skin a critter that’s already had his hide stretched on the side of the barn. I know I can strike folks as a bit of a mystery so I ain’t blind to your curiosity. I’ve set to your table so I owe you some explanations, ask away.”

❖

That was one big mouthful of words which I took to be meant to give me full access. So I made it easy for him too. I dribbled a finger of whiskey into two glasses, offered one to him and said, “Well it’s obvious you’ve been over the trail. I’d likely profit from whatever you might have to say. So, tell me your whole story but only what you are comfortable setting out to a stranger. I am not a talking man. Whatever you might choose to tell, will stay right here between my ears.”

Clint Oakley had been a mountain man, coming west from Kentucky at the age of fifteen. When his pa died, his ma had taken in a boarder for a while but just couldn’t keep up with the place. So she took up as a live-in cook with some well-off town folks. They had no work and no place for a boy.

So an uncle had taken him to the Rockies, not all that far from my Flying W, for trapping-help. But that uncle had, shortly after arriving in the Teton area, been killed by Shoshone. Clint was surprised he had escaped by hiding under a brushy log but powerful grateful to still have his hair. Throughout the next year or so, teaming up with two other trappers, he had learned purt near all a man needs for self-sufficiency on the mountain.

No, he didn’t know for sure how old he was but seeing as he had been out west and missed that entire war-between-the-states mess, which was now more than fifteen years behind us, he reckoned he was pushing late seventies. He chuckled that his bones felt like about a hundred, but insisted he could still pull his freight and give a days work for his bed and found when he rode for a brand.

His resume was impressive, though not entirely rare for a man of his age. In these times a man who’d come west would do whatever was required to earn his keep and make an honest way. He had trapped beaver and taken the plews to Rendevous where he had celebrated and bartered for his next years needs. Clint had lived with the Cheyenne and fought Sioux, Crow and Blackfoot and scouted for the U.S. Cavalry for a time. Somewhere along the way, the beaver had given out about the time the demand was going away with the fashion-switch to silk hats. He’d hunted buffalo as he needed to but found that to be disgusting work, not only because of the horrendous waste of meat but it was a sickening, filthy work.

He rode shotgun and drove stage for Butterfield. Somewhere along the way he found himself south of San Antone, purt near to the Rio Bravo and had hooked up with a short-handed cattle ranch that had mostly Mexican and Black cowboys. Those boys taught him Mex-speak, some. The wife of the ranch owner did a teaching session, for what she called “her boys,” three times a week. She had taught him his letters and numbers. Clint was some proud of his ability to cipher, read and write.

He could certainly already ride but those boys made a vaquero out of him. Before long he was riding hands-free, steering with his knees, calves and thighs, looping and dallying. He made drives up The Chisholm, The Western and even went west for a job to drive some east from Oregon after he had finished a drive pushing horns all the way to Miles City, Montana.

Then he corked the bottle and stopped sharing as suddenly and abruptly as he had willingly begun. The well had run dry. There was something there that he chose to not disclose. I respected that. I had a few things of my own that I wanted kept under my hat. Coming west and making a way wasn’t always pretty. A man did what was needed at the time and, maturing and earning some wisdom, he might look back and wish he had done differently.

We set him up for the night in the bunkhouse. There was plenty of bunk availability since the hands had been furloughed for the winter.

❖

When I walked into the cookhouse at first light, imagine my head-twist as I saw Clint Oakley, sleeves rolled up, scrubbed arms, building biscuits and bear sign alongside Cooky who was flipping flapjacks and bacon. It turned out those biscuits were the best any of us had ever tasted. Cooky said we ought to keep Clint on to lighten the kitchen load and lift everybody’s spirits. Fortunately he had not suggested it in front of Clint, as that would be something I’d have to ponder. Good biscuits or not, that was not enough contribution to keep an extra mouth around through the slack winter. But I had taken a curious liking to the old coot and he did need a place to home-up through the Wyoming winter. How was I going to work this out?

❖

I told him he could stay a few more days, give his mare some rest and fatten his belly a mite, but then he’d have to move on as I just could not see a way to make ends meet given the lean bank account from sparse cattle sales. The beef market was down and I’d chosen to only sell a much smaller than normal number of beeves. That meant more steers and heifers to feed and supplement over winter too.

Two days later, out riding and checking fences, a bank on the edge of The Green River gave way causing my mule to lose footing. We rolled down the bank in a cloud of sand with that mule trampling, falling on top of me. The saddle horn crushed me right below my diaphragm and my left leg, stirrup-hung, twisted and broke in two places.

When I didn’t show at suppertime, Clint came a’hunting me and found me as the sun was waning. He raced back to the barn, hitched up the buckboard and came after me. After splinting my leg with some gathered branches, he fetched me onto the buckboard and back to the house. He had already sent Cooky to town for the doc.

Doc Wells set my leg, saying I was lucky that somehow, the way those breaks had occurred, I’d mend up fine but it was right smart that I had been splinted to keep the damage from worsening. Examining my gut bruise, he said that I was lucky there too. If that horn had crushed me an inch or so higher my chest would have cracked and maybe busted my heart or lungs. As it was, he bound me up tight around my chest and gut and gave strict instructions to stay abed for at least a month.

❖

As I said, I was in trouble. Doc Wells predicted I’d be abed for a couple of months and likely not of much use for a while after that. I could only breathe in shallow, short, unsatisfying breaths. I constantly felt as if I was out of air. In order to sleep and still breathe, I had pillows stacked behind my back. I’d pain myself awake each night, as when I tried to shift a bit in my sleep, I’d fall off of the pillows and land on my side.

Clint brought in my dinner to my bed that night. He offered to stay on until I was all healed up. Said he didn’t want any pay, just a few squares and a dry place to sleep. He saw the skeptic in my eyes as I questioned what this stove-up old timer might or could do. At the same time, the boys I had let go were long gone, headed south to warmer climes to hunt a winter hidey hole.

He began to talk “ranching”, describing the winter chores he anticipated, the planning that needed to be done for spring, the repairs and such that would need doing and the horses that would need tending, especially the mare that was in foal. And he talked it enough, describing the chores that he could see needed doing around the place, both daily routines and neglected repair or improvements needed. Some of what he had observed and suggested to me had escaped my notice but, hearing it, I saw he was right.

He spoke the lingo. I was in a dire, needful way. I decided to find out if he would walk his talk. No man likes being so laid up so he can’t do. It’s even more aggravating when a stranger, an unknown, becomes your nurse and lead hand.

❖

It hadn’t snowed yet. Clint had taken it upon himself to ride some fence, the chore I was headed out to do when my wreck happened. When he reported back that the fences were in fair shape he also brought along some more observations.

He asked how many head we ran. I told him that we were on the heavier side of normal, probably near two thousand. Since the market had been soft, I hadn’t sold off so many, hoping to get a better price next year. He suggested adding more fences, ‘cross-fencing’ he called it.

He described how that would give us an opportunity to control our grazing and grass. We could interval-feed areas and move the cows to a fresh pasture before it got grazed too short. He told me grass that is left a touch longer will recover faster.

I had noticed a moment earlier when he had asked how big “our” herd was that he had used the word “we”. Now he was using the word “us”. These possessive pronouns, coming from a near-stranger, rankled a man flat on his back who wouldn’t likely be of any use at all for more than a month and maybe two or more.

❖

Recovery was slow but that was only my perspective. The doctor said I was doing remarkably well. After six weeks he released me for light duty. If I traveled it would have to be in a wagon.

It was early December, coming on to Christmas. I was using crutches as I stepped outside onto the veranda. I knew I had lost strength but the reality hit when I had to sit on the porch swing after only crutch-walking from my bedroom.

So I sat and looked around the yard, at the bunkhouse, cookhouse and barn and fences. It was right pleasurable to be outside breathing the cold winter air. There had not been a lot of snow so far. Someone, apparently Clint, had whitewashed those buildings, including the outhouse. I could see that some roof repairs had been made and that he had rearranged those corral rails the way he had suggested to me a couple months back when he had first arrived. Twisting I glanced back at the house itself and noticed that not only had he painted it too, but he had built a pretty little picket fence around the veranda.

Who was this man?

❖

A month later I was about as good as new. Oh I had a bit of a limp as I favored that leg, but my bruised gut and chest had all healed up. I could ride again and do a little work. I was just in time as a fierce, Wyoming winter storm blew in the next day. It dumped something close to two feet of snow in just a couple of days.

As most of our storms came raging out of the northwest, I had built the barn doors on the southeast side of the barn. Together, Clint and I cleared away the snow so we could get the barn doors open. We went in to check on the horses and found that the mare had foaled the prettiest little buckskin colt. Together we laughed as it wobbled on those long, spindly legs. The laughter was soothing and a thing I hadn’t done for a long while.

❖

Clint spoke to me a week or so later as we enjoyed some flapjacks and burnt coffee.

“Will, I reckon it’s time for me to move on seein’ as you’re ‘bout all healed up. A deal is a deal and I sure have appreciated a place to lay up.”

The gospel truth is, that was a gut-kick to me. I hadn’t much thought about his leaving and, fact is, Clint had become a piece of the operation and like a family member. Thinking of his leaving left a hollow ache in my throat.

I’d worked long and hard to set my ways and methods. I had studied and taken notes, sometimes mental and sometimes in a journal, as to what worked and what didn’t, what was a waste of time and what got the job done. The best way, which was often not the easy way, was where my interest lay. I was concerned with results and outcomes and had not come upon my methods, or my trust in them, by chance. I was a man with a plan and a purpose.

Still, though they had proved to be useful and worthy, and I generally found no reason to change them, only a fool wouldn’t listen to advice or observe new practices from a sage when such a gift presents. I'm not generally inclined to take a lot of advice, and I’m right selective about who I listen to. But Pa, who had spent time sailing around The Horn, had been fond of reminding me, “One sign of a good knot was that it should be easy to untie. So keep your knots on the easy side because a new wind can make a sailor need to trim his sails.”

I hadn’t liked being laid up. I had been uneasy with Clint Oakley taking over the place, but that was plumb-stupid seeing as I was unable to do anything and he had made things better. At first, I hadn’t much cared for the way he approached tasks when his ways were not what I was used to. But they had worked and, in most cases, worked better.

It came to me that the wind had shifted, putting my ranch on a broad reach. I loosed my knots and trimmed the figurative sails of how the Flying W was gonna be run.

“Clint, any chance you might see your way to stay on permanent, call me Willy and keep making biscuits?”

❖

by Rik Goodell

© 2024 All rights reserved

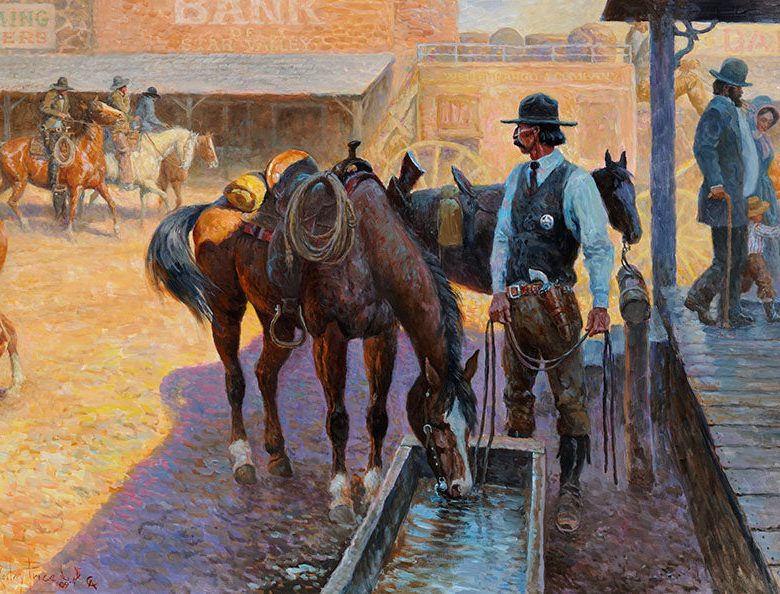

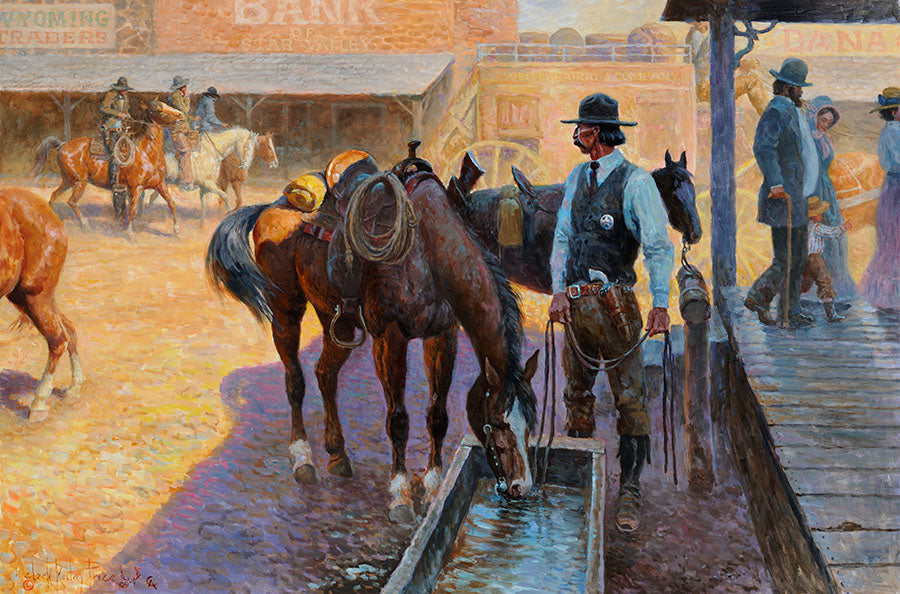

This painting of a cowboy heading out to work is the artwork of my friend, Gregory Mayse.

To see more of his fine art, visit his website:

"Back At It", by Gregory Mayse